Shibari Kinbaku as a Ritual:

Protocol for viewers and models (Part I)

Copyright 2011 by Haru Tsubaki & KinbakuMania. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher

This is the first of a series of articles I’ve written with my mind set on those who have their first encounter with Shibari/Kinbaku. Whether you do it as riggers, as a model, or simply as mere spectators, there are many matters, codes and traditions that must be respected to maintain this harmonious art as it is lived all over the world, and especially where it was born, in Japan. I hope you’d enjoy the reading and also this would humbly help enlighten you about this wonderful art, helping you build better moments when you watch or practice Shibari/Kinbaku.

Why we say Shibari is ritual?

No one stops learning even in Shibari/Kinbaku’s world… We’re all embedded in an endless journey where we’ll never quit being students in perpetual learning. A teacher may be that one who has already traveled farther and therefore got more experience willing to guide and accept us as his students. A Sensei (teacher) is that person who manages a ryu (school) where everybody learns. He also learns by the act of driving his knowledge and passing it to whoever he considers appropriate.

In the same way as in origami (the art of paper folding), ikebana (the harmony of flowers), sado (the ancient tea ceremony tradition) or even in the preparation of a traditional sushi had become in highly ritualized arts, it happens in the same way in Shibari (Japanese bondage). Having that in mind I thought it might be useful to share with you what I’ve humbly learned (from my Senseis’ generous teachings) about this. I must say I’m doing this with the sincere intention to help improve the respectful relations between riggers, models, viewers, teachers and students. I will only write about those aspects I’ve learned as good practices, about ethical codes, and also about “honor matters” in Shibari/Kinbaku. Many of this details may seem simple protocol, but are intimately related to health and security cautions. In a nutshell “we can have fun and enjoy, being respectful and responsible at the same time.”

About its origins and the inherited traditions

Going back in history we’ll find that Shibari/Kinbaku had its ancient origins in the arts of the war (Hoshu Hojojutsu), the tradition of castes, Clans, Shoguns, Samurais and their overlords who were ruled by a very strict warrior honor code called Bushido. It’s therefore a normal consequence that a similar ethical code had driven Shibari/Kinbaku since its origins and became an “honor code” between those who practice and those who love ropes even when they don’t practice it.

Going back in history we’ll find that Shibari/Kinbaku had its ancient origins in the arts of the war (Hoshu Hojojutsu), the tradition of castes, Clans, Shoguns, Samurais and their overlords who were ruled by a very strict warrior honor code called Bushido. It’s therefore a normal consequence that a similar ethical code had driven Shibari/Kinbaku since its origins and became an “honor code” between those who practice and those who love ropes even when they don’t practice it.

From that time where the 18 Samurai warrior skills were taught, were rope skills (Hoshu Hojojutsu, the ancestor of what is Shibari/Kinbaku nowadays) was one of them, these capital rules were born, deeply based in that ancient Bushido Japanese culture context. Those same principles, even when slightly modified, are what is considered the cornerstone of today’s Shibari/Kinbaku.

These were the four main rules in Japanese bondage:

1. You shall never let your prisoner escape from the bonds

2. You shall never harm physically or mentally your prisoner.

3. You shall never let other clans see the techniques.

4. Your tying should be beautiful, balanced and artistic.

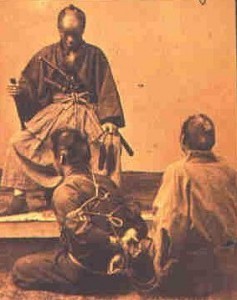

These rules evidently spoke about “prisoners” since they were related to that war skill used by Samurais to capture and transport prisoners to the courts on those days. The different rope color, and the many tying patterns were clear signs of both the crime they were accused, and the social cast they were from.

This situation, between the rigger (Samurai) and the tied one (prisoner) used to be very ritualistic. Both the public exhibition of the prisoner to the people that watched him walk in front of the Samurai heading to the court, and the prisoner deliver itself to the magistrates, were a humiliating but also a highly honorable act for the prisoner. That duality between humiliation and honor, that we may see contradictory, was possible by the high respect for the manners that both Samurai and prisoner had.

In today’s Shibari situations are quite different in many aspects, but closely similar in others. We don’t handle prisoners, we don’t speak about trials, courts, or magistrates as in Japan’s Edo period, but we definitely keep those honor concepts in our tying rituals. We also keep Shuuchinawa (the soft rope caressing style that leads to humiliating and distressing situations) and Semenawa (rope torture) as the two typical ways a Shibari/Kinbaku session may lead to. Whether it would go one way or the other depends on what the rigger perceives on the model’s mood on that moment.

In today’s Shibari situations are quite different in many aspects, but closely similar in others. We don’t handle prisoners, we don’t speak about trials, courts, or magistrates as in Japan’s Edo period, but we definitely keep those honor concepts in our tying rituals. We also keep Shuuchinawa (the soft rope caressing style that leads to humiliating and distressing situations) and Semenawa (rope torture) as the two typical ways a Shibari/Kinbaku session may lead to. Whether it would go one way or the other depends on what the rigger perceives on the model’s mood on that moment.

What is a Shibari/Kinbaku session about?:

As we said before, Shibari/Kinbaku practice is not only considered as a mere tying act. Kinbaku is a way of beauty, functional and safe tying that involves a whole range of aspects. The basic movements that are used to manage the ropes can be related to those you apply to the brush when you practice Japanese calligraphy (shodo 書道). The tying process should always have high visibility (taking in account the observer point of view). Along all this process there should always be intensity and energy transfer present between rigger and model (ki hairimasu). The rigger should be always aware of any kind of signals coming from the model (AKA “the all seeing eye” or “peripheral vision”). Rigging should have an aesthetic quality both in the functional parts as in its decorations (kazarinawa). The rigger should always handle the ropes with skill and efficacy (sabaku 捌く ). The rigger should be able to wisely vary the tying pace (merihari 減り張り), listening to the internal rhythm of the model to wisely take advantage of it without being selfish. He should wisely engage both in his spatial position and distance between him and the model, the engagement angle, and the engagement speed to perform his rigging (maai 間合い). He should be able to know how and when to apply the hidden or secret techniques (urawaza 裏技), and be able to achieve the (muganawa 無我縄) “not self” mental state, to take the best of that moment.

As we said before, Shibari/Kinbaku practice is not only considered as a mere tying act. Kinbaku is a way of beauty, functional and safe tying that involves a whole range of aspects. The basic movements that are used to manage the ropes can be related to those you apply to the brush when you practice Japanese calligraphy (shodo 書道). The tying process should always have high visibility (taking in account the observer point of view). Along all this process there should always be intensity and energy transfer present between rigger and model (ki hairimasu). The rigger should be always aware of any kind of signals coming from the model (AKA “the all seeing eye” or “peripheral vision”). Rigging should have an aesthetic quality both in the functional parts as in its decorations (kazarinawa). The rigger should always handle the ropes with skill and efficacy (sabaku 捌く ). The rigger should be able to wisely vary the tying pace (merihari 減り張り), listening to the internal rhythm of the model to wisely take advantage of it without being selfish. He should wisely engage both in his spatial position and distance between him and the model, the engagement angle, and the engagement speed to perform his rigging (maai 間合い). He should be able to know how and when to apply the hidden or secret techniques (urawaza 裏技), and be able to achieve the (muganawa 無我縄) “not self” mental state, to take the best of that moment.

That energetic exchange between rigger (bakushi 縛師) and model is meant to create a strong communion and connection between them where the rigger carefully “listens” what the model energetically wants (muganawa). Muganawa (無我縄) refers to the rigger’s way to face the session by emphasizing the idea of getting the model reach his/her true potential rather than trying to impose rigger’s will. “Muga” (無我) is a Buddhist concept that refers to the absence of one self, the clearing of our minds, and letting our own wills aside.

Other of the many interesting aspects of Shibari/Kinbaku is that inside the techniques, the viewer’s point of view is always present. Even when there may be no one watching the act, everything is done as if there is a viewer. Keeping that in mind it’s considered good manners that the rigger would perform the tying showing confidence both to the model and the viewers. At the same time he’ll always show the best of his model, her reactions (both on her body and on her face), and her more sensual aspects.

What should I keep in mind when I model or witness a Shibari/Kinbaku session?

– In the same way that in the Edo Period it was considered “honorable” to deliver the prisoner to the magistrates in a functional and beautiful way, and that the Samurai was evaluated for the way he tied the prisoner and not by himself; in the same way in a Shibari/Kinbaku practice the one who should shine is the model, and never the rigger. It’s considered good manners that the rigger would excel only through his models and the reactions he gets from them with the ropes.

– Once the session started, whether it is private, a training or a public performance, it is considered a ritual. A good viewer should never try to interact with the rigger or the model without having arranged it previously with the rigger. It’s also not smart and considered bad manners to get too close. The rigger needs an ideal 12 feet free space around to be able to work comfortable. Rope speed is many times too high and may unwittingly hurt those too close. In case that happens, do not disturb the rigger, since it’s your fault (and no one else’s) for not having respected his space.

– The experience a good rigger would bring to the model and the viewers would be unique and unrepeatable. It’s considered an honor matter that the viewers would show respect to it keeping silent and expectant.

– It’s not a good idea to touch anyone else’s ropes. Don’t try to handle them to the rigger or pick them from the tatami while he’s untying. The ropes (nawa 縄) are very precious and personal objects for each rigger, in the same way they were for the Samurais. This goes beyond any physical concept involved. Besides the ropes are made of live natural fibers (hemp or jute) that react to pressure, temperature and humidity variations, they’re also the tool the rigger has to transmit his energy flow “ki”. Ropes are so important, as they are the way the rigger has to communicate his “self” to the model, to the viewers and to the cosmos as a whole.

– It’s highly usual that something may have call your attention during the session. But in order not to break the mood and the energy flowing during the session it’s good manners to wait to the tying to be over (when the last rope have been taken off from the model’s body and sometimes after the rigger thanks the audience) to ask for permission to present your questions to the rigger.

– If you happen to meet the rigger after the session is finished, it’s good manners to first thank him for your recent Shibari experience before asking anything you want.

– A good model is the one that surrenders to the ropes experiences and lets that inner journey the rigger is about to drive him flow (Indou wo Watasu 引導を渡す , as it is called in Yukimura-ryu) without any inhibition of being in a high energetic permeability state to rigger. This insight attitude often reflects into physical non verbal expressions on model’s body like having the legs together and slightly bent, keeping the thumb flexed inside the palms of the hands, having a relaxed body, arms to the sides, eyes downcast or feet pointed slightly inwards. “The all seeing eye ” of the rigger must clearly perceive all these signals from the model and react accordingly.

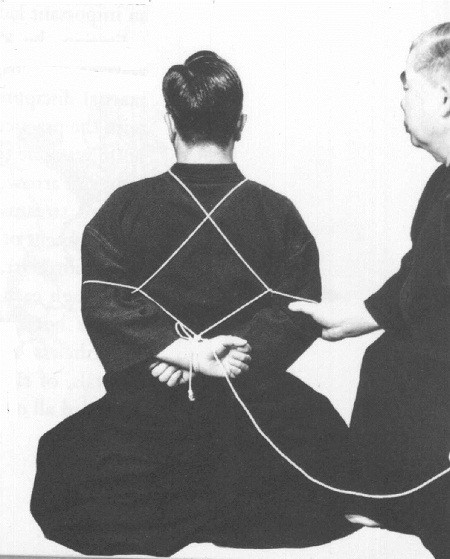

– Another model’s posture often used to calmly wait is called seiza. It’s used in several other martial arts also. You kneel down with your knees one fist apart if you are a woman, or two fist apart if you are a man as shown in the picture.

– If you’re letting this particular rigger tie you is because you trust in his ability and skills. Many models consider themselves honored by the experiences they’re given through the ropes. It will be considered highly offensive if the model tries to get free of the ties or if they’re not considered seriously.

– It’s not good manners to “help” the rigger in any way, handle him things, to talk during the session (breaking the mood), or even to put your arms behind your back before the rigger had done anything. You would recognize a good Shibari/Kinbaku rigger because he will not need you to put your arms in any special position. He would manage to do exactly as he wants with the position of your arms.

– It’s mandatory to practice this art being on bare foot, mainly because the ropes are made of jute (and thus they can’t be washed). Stepping over a rigger’s rope as a viewer is considered as a unacceptable disrespect. We have said before that ropes are used to transmit rigger’s energy (ki). Stepping over them is like stepping over the rigger’s most intimate part. Stepping over them wearing any kind of footwear is even a worse offense. Only the rigger and the model are allowed to step over the ropes during the session.

– The rigger is responsible for looking after model’s safety and wellbeing all along the session. That process does not end until the last rope is taken off the model’s body by the rigger. Unless there is some special case, it’s considered bad manners to let the model untie by himself / herself or to delegate that task to anybody else (there are special cases where a Sensei commands a student to do that task, but in that case it is used for teaching purposes).

– It’s usual that a rigger would let the ropes fall over the tatami as he unties them from the model’s body. Those ropes are not to be touched by the viewers and would only be recoiled again by the rigger or by someone he/she specially designates to do so. It’s considered a high honor for an apprentice to be chosen to recoil his Sensei’s ropes (nawa).

I think this summarizes a bit of the ancient origins and the reasons for the many situations that you may face during a Shibari/Kinbaku session between rigger, model and viewers. There may be certainly much more to talk about this and there may be many questions left unanswered. You can share your questions here or contact me to ask them privately if you want. One way or another we’ll keep learning together.

Note from the author: It’s considered disrespectful to use Japanese terms or concepts to describe occidental bondage practices or ties..

Next article in this series is: Shibari Kinbaku as a ceremony: Interaction between rigger and models (Part II) where I’ll address concepts related to the rigger, the rigging and the model.